- “Anal cancer is rare, but much more common in people living with HIV and immune deficiencies.”

- “This type of cancer is preventable by screening and successfully treatable when caught early.”

- “Screening is quick, safe and often part of routine care.”

- Use supporting evidence if you think it would helpful

- “People living with HIV are at significantly increased risk to develop anal cancer.”

- “Screening and treatment of pre-cancers reduce anal cancer risk by 57%.” (Stier et al., 2024)

- Normalize screening:

- “This is like a cervical Pap test, but it is done for the anus.”

- Normalize symptom reporting by asking direct, stigma-reducing questions, such as:

“Have you noticed any anal problems like itchiness, bleeding, lumps, pain or discomfort?”

Supporting Anal Cancer Screening in Primary Care for People Living with HIV

People living with HIV are at significantly increased risk (20 to 60 times) for anal cancer, primarily due to immunosuppression and persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. Despite this risk, routine anal cancer screening remains incomplete and inconsistent across Canada due to a lack of clinical guidance and limited provider and patient awareness.

This tool supports primary care providers in the early identification, screening and follow-up of anal precancer, specifically high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) among people living with HIV. Developed through a knowledge translation process and informed by high-quality guidelines and implementation research, the tool promotes a proactive, evidence-based approach that integrates anal cancer screening into routine HIV care.

Note: While anal cancer screening is also recommended for other at-risk populations beyond people living with HIV, this tool is specifically focused on supporting screening within HIV primary care settings. As such, recommendations for broader populations are outside the scope of this resource.

What we are screening for

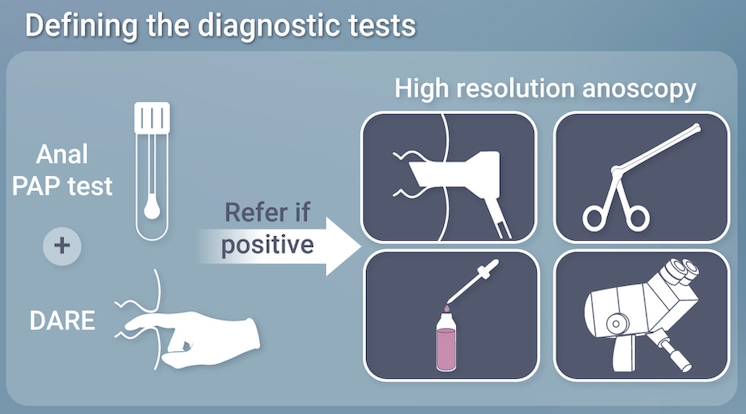

Anal cancer screening aims to find anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions which are HPV-associated precancerous changes that come before most anal squamous cell carcinomas, and to detect early cancers when they are still localized. In practice, screening uses anal cytology and/or high-risk HPV testing, with Digital Anal Rectal Exam (DARE) performed at the same visit. Individuals with abnormal results are further evaluated with high-resolution anoscopy (HRA) and biopsy. In settings without HRA access, performing DARE routinely in at-risk populations is recommended to help identify early cancers. (Stier et al., 2024)

Who to screen

Anal cancer screening using DARE or DARE with anal pap swab is recommended for people living with HIV:

Starting at age ≥35 for men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women (TW)

Starting at age ≥45 for all others

(Stier et al., 2024)

See International Anal Neoplasia Society (IANS) Screening Population Table for risk categories and age thresholds.

High Resolution Anoscopy

HRA is used to detect lesions otherwise not perceptible using regular anoscopy. It involves the following:

- An anoscope is inserted

- Two solutions are used: acetic acid and Lugol’s iodine, to stain the anal tissue

- Anus is then examined with a colposcope under magnification

- Anal high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) have characteristic staining patterns that will appear

- Any lesions identified are then biopsied

(Andrews, et al., 2025)

Note there are limitations due to availability of HRA clinics. It is important to first determine if there is an HRA clinic in your region and to check with the clinics beforehand to see their wait times and their capacity for screening the various results from the anal swab.

See list of HRA clinics below.

Why is screening needed?

People living with HIV, especially men who have sex with men (MSM), face a significantly higher risk of developing anal cancer compared to the general population. (Clifford et al., 2020; Spindler et al., 2024; Chromy et al., 2025; Hirsch et al., 2025)

Early detection through screening and appropriate treatment can reduce the risk of progression of HSIL to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) by about 57%. (Palefsky et al., 2022)

Recognizing and responding to symptoms New

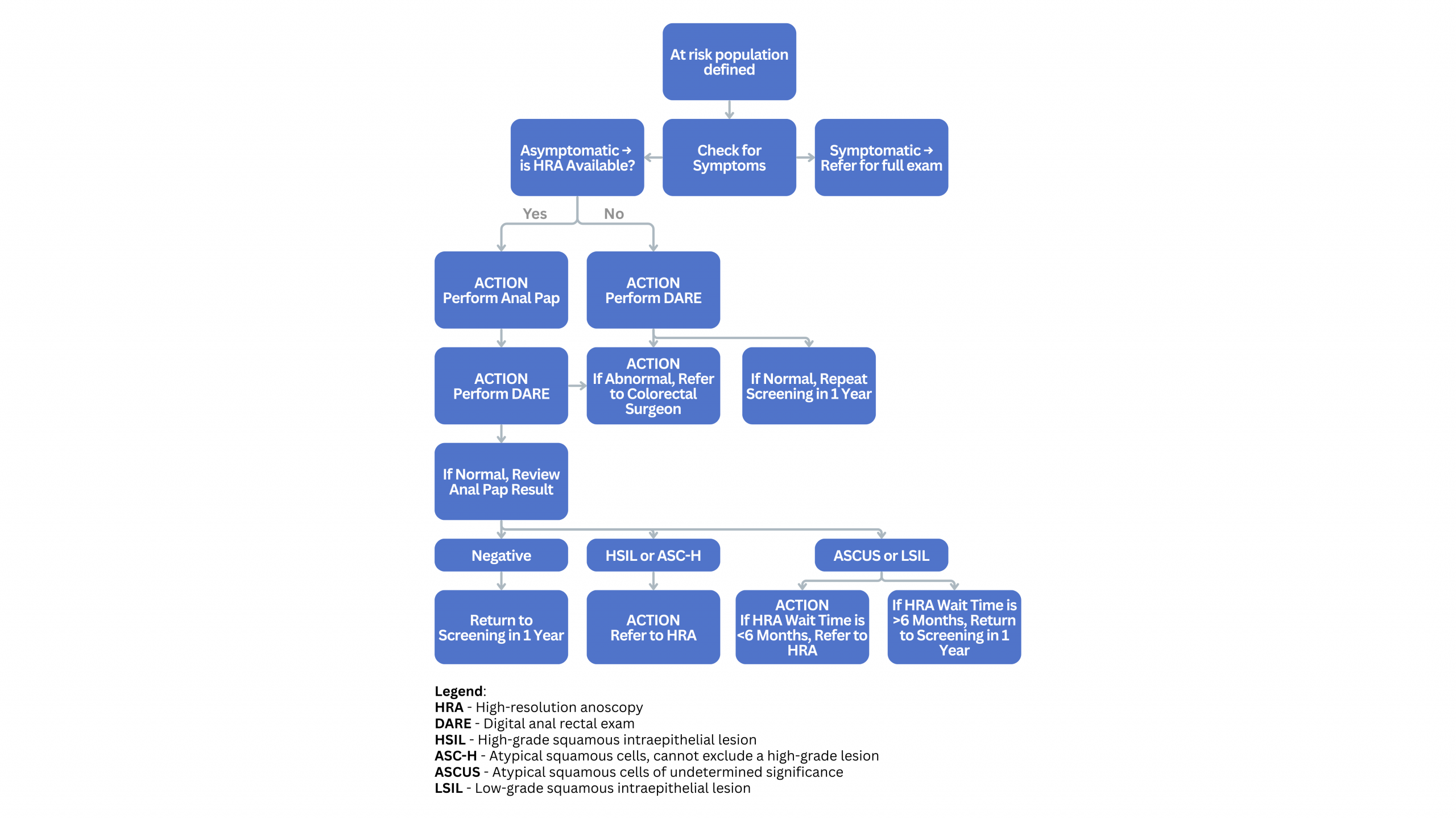

Anal cancer screening is intended for asymptomatic individuals at elevated risk. When patients present with anorectal symptoms, they require diagnostic evaluation, not routine screening.

Common symptoms to ask about which could suggest anal cancer are:

- Anal pain or itching.

- Bleeding, particularly during bowel movements.

- A sensation of fullness or a lump in the anal canal.

- Perianal lesions.

What to do next

If a patient presents with any of these symptoms, primary care providers should:

- Take an anal history to support appropriate evaluation.

- This may include asking about: sexual history, history of warts, anal intraepithelial neoplasia, hemorrhoids, fissures, fistulas, or prior anal surgery. (Hillman et al., 2019)

- Perform a DARE

- Refer the patient to a colorectal specialist, for further assessment with or without a preceding imaging procedure (expert opinion, Hillman et al., 2019, Hirsch et al., 2025; Stier et al., 2024, Chromy et al., 2025)

What to say: Education and engaging patients in screening

Education improves screening uptake; knowledge is often limited in patients and is an important step that should not be overlooked (Wheldon et al., 2023). Stigma, embarrassment, and provider discomfort are top screening barriers (Sam et al., 2025). Affirming communication improves trust and participation (Stier et al., 2024)

Key messages and communication tips

- Use inclusive, non-judgmental language.

- Acknowledge stigma and cultural barriers.

- Be transparent about what the exam involves to reduce fear and uncertainty.

- Use plain-language explanations and visual aids where possible.

- Share the patient tool/handout.

Health equity lens

- Black, Indigenous, and racialized people lving with HIV report lower screening rates. (Gillis JL et al., 2020, Hirsch et al., 2025)

- Address barriers such as stigma, distrust and access.

- Use gender-affirming and anti-racist care principles.

Patient education materials and approachable resources are available in the IANS toolkit under “Patient Education”.

Preparing to screen

Ensure your clinic is properly setup/prepared for screening:

- Review whether patients with abnormal Pap tests can be sent for high-resolution anoscopy (HRA).

- If HRA referral is possible, do Pap + DARE

- If no HRA referral is possible, only do DARE

- Infrastructure and exam room readiness

- Ensure appropriate exam space: clean, private, with adjustable examination tables.

- Stock supplies: gloves, lubricant, proper swabs (Dacron), patient gowns, cleaning materials, liquid cytology bottles.

- Confirm EMR templates or screening documentation forms are in place for data capture.

- Review talking points in “What to Say: Education and Engaging Patients”

How to screen: Recommended practices

Jump to:

Annual screening is recommended for people living with HIV. (Hirsch et al., 2025; NIH, 2024) The primary objective is to identify abnormal cytology or any palpable abnormalities that require further evaluation. (Hilman et al, 2016)

Anal Cytology (Pap test)

Anal cytology should be performed before the DARE, as lubricant can interfere with specimen quality. It should only be done if referral for HRA is available for abnormal results (Spindler et al., 2024).

How to perform Anal cytology

- Insert a water-moistened polyester Dacron swab (tap water is sufficient) into the anal canal as far as it can go. Rotate firmly 360° in the anal canal while applying firm lateral pressure so that the swab bends slightly.

- Slowly withdraw the swab over 15 to 30 seconds, maintaining the circular motion throughout the withdrawal (Expert Opinion).

- Insert swab in liquid cytology medium. Shake the swab vigorously in the liquid and discard the swab. (Spindler et al., 2024)

For more information, see IANS Anal Cytology Collection Video.

DARE

Preparation (Hilman et al., 2016)

- Do a risk assessment (documenting symptoms, relevant behaviours and anal history)

- It should be part of routine care but informed consent should be obtained

- If anal cytology, HPV DNA, or other sexually transmitted infections are planned for testing, do these tests before the DARE.

How to perform a DARE

The following steps outline the procedure when the patient is positioned in the left lateral position:

- Explain the procedure, ensure patient privacy, and obtain informed consent.

- Apply generous lubricant to the gloved index finger (a topical anesthetic may be used if a high-resolution anoscopy is planned).

3. Gently part the buttocks with your non-dominant hand to expose the anus.

4. Lubricate the anal verge, then gently press on the sphincter to encourage relaxation.

5. Once relaxed, insert the lubricated finger slowly until reaching the free rectal space (typically past the anorectal ring).

Choose one of the following techniques:

Option A: Longitudinal sweeps

- 6. Start in the proximal rectum and apply gentle lateral pressure.

6a. Withdraw slowly while palpating distally toward the sphincter.

6b. Reinsert and rotate finger 30° counter-clockwise, overlapping each area to ensure full coverage.

6c. Perform a circumferential sweep of the entire anorectal canal.

Note: Pay special attention to:

- Posterior space

- Anterior walls and prostate (in men) or cervix/uterus (in women)

Option B: Circumferential sweeps

6. Use a continuous circular motion throughout insertion and withdrawal, covering all rectal and anal canal walls.

Note: Be mindful of the anterior aspect, which is easily overlooked.

7. Assess posterior and anterior walls; in men, palpate the prostate; in women, the cervix or pouch of Douglas.

8. Use the finger pad to evaluate lateral and distal regions of the anal canal.

9. Identify any tenderness, nodules, asymmetry, or other abnormalities.

10. Inspect the glove for blood or discharge.

11. Repeat the exam if coverage was incomplete or findings are unclear.

Note: A thorough DARE may take up to 1 minute. With practice, clinicians can complete it more efficiently while maintaining patient comfort.

Note: Lesions can be very small, sometimes as small as a pinhead, so even subtle findings on palpation are worth assessing closely.

For more information, see IANS Anal Cytology Collection Video. For more information refer to the:

- IANS toolkit for cytology supplies and DARE videos.

- IANS Guidelines for the Practice of Digital Anal Rectal Examination.

- IANS Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) section addressing common clinical questions related to screening and test interpretation.

What to do next: Referral and follow-up

Specialist wait-times can be long, but referrals should still be made promptly, as timely referral improves outcomes (Hirsch et al., 2025). Symptomatic patients require immediate evaluation (Spindler et al., 2024). Refer to an anorectal or colorectal surgeon if a mass or other concerning symptoms are present.

Referral guidelines

Refer abnormal cytology or hrHPV results, or any concerning DARE findings, to specialists trained in HRA.

If HRA is unavailable, consider anoscopy and biopsy by experienced clinicians. While specialists typically manage treatment and follow-up for patients diagnosed with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), it’s important for primary care providers to understand what this process may involve supporting ongoing care and patient education.

There are two main clinical pathways after referral:

- If no disease is found on HRA, the patient is usually referred back to the primary care provider for annual anal cancer screening.

- If HSIL is confirmed on HRA, the patient will remain under specialist care, with HRA follow-up every six months until two consecutive negative exams. If stable and pre-cancer free, surveillance can transition into longer internals (i.e., every two to three years) or they are referred back.

List of HRA Clinics

Address: 580 Harwood Ave S. Ajax, ON L1S 2J4

Tel: 905-576-8711 x53127

Fax: 905-665-2409

Note: Expecting to open external referrals to physicians outside of Durham region later in 2026.

Address: 585 University Ave. Room 13, North 1300. Toronto, ON M5G 2N2

Tel: 416-340-4800 x 8172 (Tues & Thurs)

Fax: 416-340-4890

Attn: Early Anal Cancer Screening

Note: HRA is performed in an outpatient setting with the patient awake

Note: TGH review all referrals, but only accept referrals for people who are:

- Living with long-term immune suppression e.g living with HIV or living with solid organ transplantation (10 years out from transplant) or taking long-term immune suppressing medication AND

- Over age 35 years AND

- Have a current finding out HSIL or ASC-H on anal Pap or HSIL on anal biopsy.

Note: Clinic does not accept out-patient clinics, however only if the treatment requires the operating room.

Address: 501 Smyth Rd. Ottawa, ON K1H 8L6

Fax: 613-737-8164

Note: Accepting referrals for HIV+ individuals with HSIL on anal Pap

Disclaimer: Referring physicians are responsible for confirming patient eligibility, referral requirements, and current availability of services with the clinics listed above.

Training Opportunities

To support increased access to HRA, the Ontario HIV Treatment Network (OHTN) periodically offers open calls and training opportunities for clinicians interested in developing HRA expertise. For more information, see Health HIVe: an OHTN Education Portal.

Additional Resources

IANS Anal Cancer Screening Tool Kit: A comprehensive collection of clinical guidance, practical tools, instructional videos, patient education materials, and referral resources to support implementation of anal cancer screening in clinical practice.

References

-

[1]

Hirsch et al. (2025). NYSDOH AIDS Institute Guidelines.

-

[2]

Chromy et al. (2025). German-Austrian Guideline on Screening for Anal Carcinoma in PLHIV.

-

[3]

Gillis JL, Grennan T, Grewal R, et al. Racial Disparities in Anal Cancer Screening Among Men Living With HIV: Findings From a Clinical Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;84(3):295-303.

-

[4]

Spindler et al. (2024). French Recommendations for Clinical Practice.

-

[5]

Stier et al. (2024). International Anal Neoplasia Society Consensus Guidelines.

-

[6]

NIH, CDC, HIVMA, IDSA. (2024). Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections.

-

[7]

Sam et al. (2025). Systematic Review of Screening Barriers Among MSM

-

[8]

Palefsky et al. (2022). Treatment of Anal High-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions to Prevent Anal Cancer

-

[9]

Hillman, Richard John MD; Berry-Lawhorn, J. Michael MD; Ong, Jason J. PhD; Cuming, Tamzin MD; Nathan, Mayura MD; Goldstone, Stephen MD; Richel, Olivier MD, PhD; Barrosso, Luis F. MD; Darragh, Teresa M. MD; Law, Carmella MD; Bouchard, Céline MD; Stier, Elizabeth A. MD; Palefsky, Joel M. MD; Jay, Naomi PhD. International Anal Neoplasia Society Guidelines for the Practice of Digital Anal Rectal Examination. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease 23(2):p 138-146, April 2019.

-

[10]

Clifford et al., (2020). A meta-analysis of anal cancer incidence by group: Toward a unified anal cancer risk scale.