COPD assessment test (CAT)

CAT score interpretation:

>30: very high

>20: high

10-20: medium

<10: low

This tool is designed to support family physicians and primary care nurse practitioners in identifying and managing COPD in adult patients.

Case finding for COPD in the general population has been helpful in identifying persons to screen for COPD. Screen adult patients presenting with symptoms of COPD to support early detection.

Symptoms of COPD are similar to those of asthma. However, COPD is unlikely in patients younger than 40 and diagnosis is dependent on a history of exposure to risk factors.

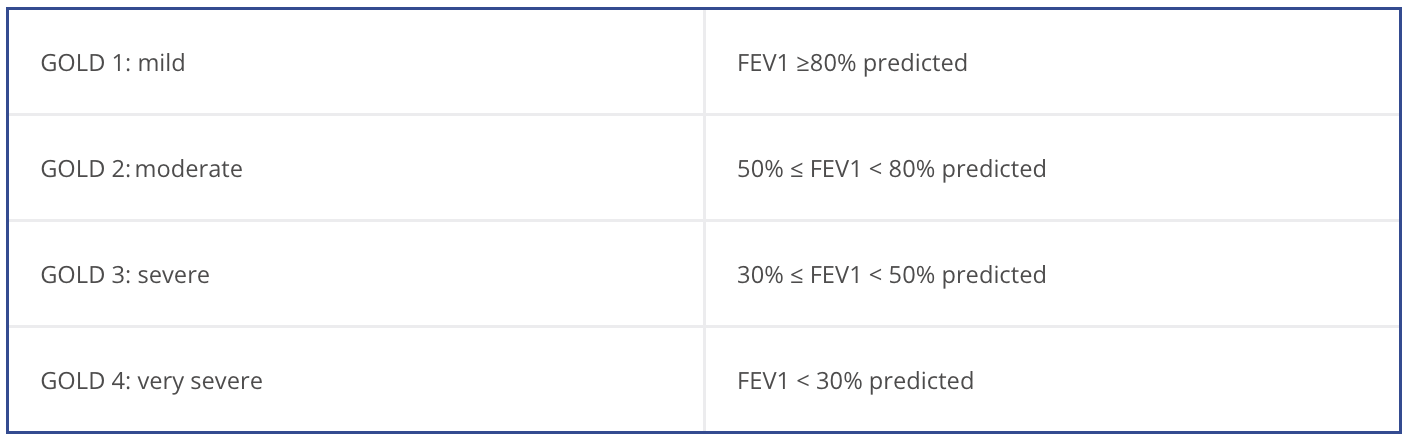

In patients who screen positive for symptoms and risk factors, use forced spirometry to establish a diagnosis of COPD.

Although spirometry should be done within three months of developing symptoms, if access to spirometry is a barrier and there is a high degree of suspicion of COPD in a patient, therapy may be started on speculation.

For a full spirometry interpretation flowchart see the Lung Health Foundation – Spirometry interpretation guide

Rule out the following conditions before confirming a diagnosis of COPD:

*Differentiating asthma from COPD in adults may be clinically difficult but is important as they differ in first-line therapies and chronic management. Asthma can present as wheezing and chest tightness that is common at night, whereas COPD can present as morning cough that produces phlegm. Additionally, patients with asthma are more likely to have allergic or atopic dermatitis (eczema).

Once COPD has been diagnosed, evaluate the severity and magnitude of the disease by assessing the degree of disability, past medical history, and previous history of moderate and severe exacerbation.

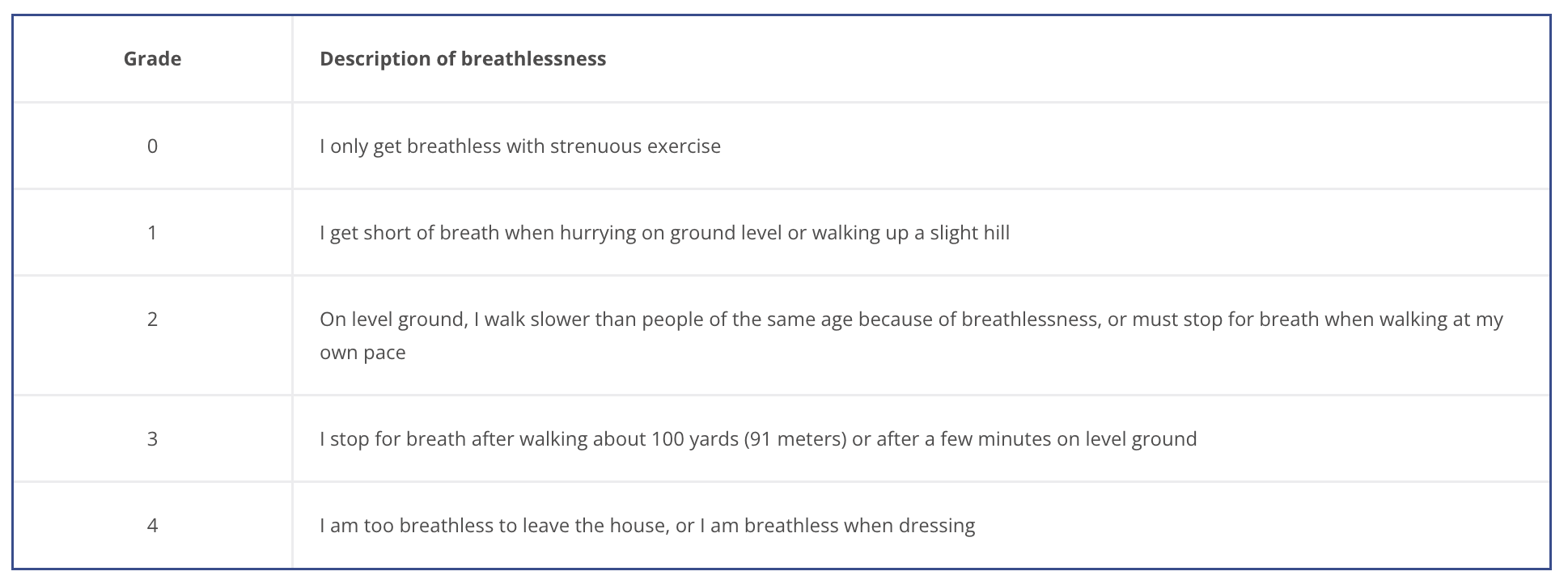

The degree of COPD related disability depends on symptom severity, and can be measured using:

>30: very high

>20: high

10-20: medium

<10: low

Exacerbation is associated with increased rates of hospitalization and disease progression and can vary greatly between patients. Identifying patients with frequent past exacerbation will help to identify the severity of disease and those susceptible to exacerbation.

The best way of identifying the severity of disease and patients susceptible to exacerbation is through exacerbation history:

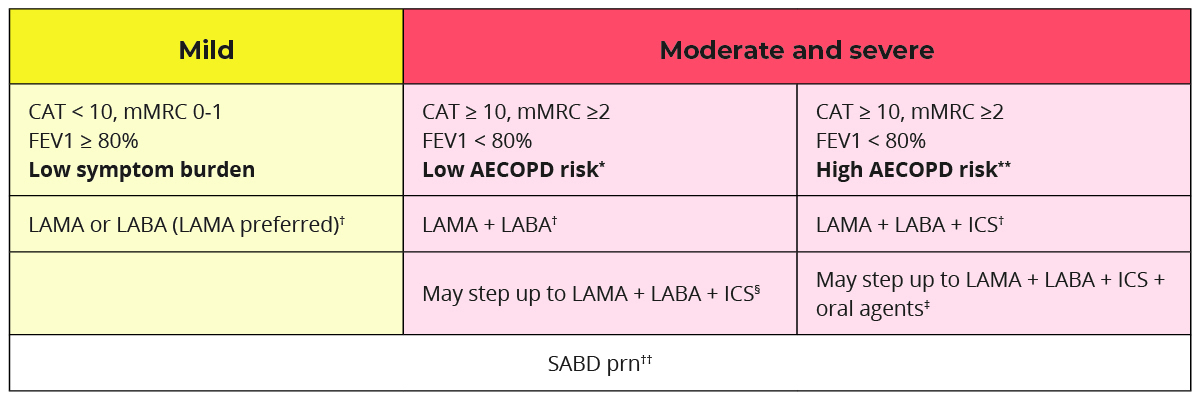

Choose medications based on cost and clinical response balanced with side effects. Individualize the treatment regimen as the relationship between symptom severity, airflow obstruction, and exacerbation severity differs with each patient. Initial management should address reducing exposure to risk factors, managing comorbidity, alleviating dyspnea (mMRC), improving health status (CAT), reducing the risk of acute exacerbation and mortality.

Choose initial medication based on past exacerbation and severity of disease.

* Low AECOPD risk = ≤1 moderate AECOPD in the last year (moderate AECOPD is an event with prescribed antibiotic and/or oral corticosteroids) and did not require hospital admission/ED visit

** High AECOPD risk = ≥2 moderate AECOPD or ≥1 severe exacerbation in the last year

† A single inhaler containing a combination of medications is preferred; however, separate inhalers may be used based on patient preference. LAMA+LABA is generally preferred over ICS+LABA (except in patients with concomitant asthma) because of additional improvements in lung function and the lower rates of adverse events such as pneumonia.

‡ Oral agents include prophylactic macrolide/PDE-4 inhibitor/mucolytic agents.

§ Consider stepping down to LAMA + LABA if LAMA + LABA + ICS did not result in improved symptoms or health status or because of adverse effects of significant importance.

†† Short-acting bronchodilators include SABAs (short-acting beta-2 agonists) and SAMAs (short-acting antimuscarinics), and are used for as needed relief of episodic dyspnea. SAMAs should not be given as short-acting relief in those also prescribed long-acting muscarinic therapy due to the cumulative anticholinergic side effects.

LAMA = long-acting antimuscarinic agent

LABA = long-acting beta-2 agonist

ICS = inhaled corticosteroid

Combining bronchodilators that have different mechanisms and durations of action can increase bronchodilation with a lower side effect risk. The combination of LAMA + LABA significantly improves lung function, dyspnea, health status, and reduces exacerbation rates in comparison to monotherapy with a LAMA or LABA. There are numerous combinations of LABA and LAMA in a single inhaler, which is preferable to using two separate inhalers.2

Poor adherence could lead to:

To improve adherence:

Review the patient’s risk of exacerbation, symptom burden, and comorbidities at least annually.

Reduce symptoms*

Reduce risk*

If patient is not achieving goals of therapy:

Oral medications may be considered (in consultation with a specialists) if a patient has maximized use of inhaler therapies (additional use details below).

Macrolide antibiotics (azithromycin)

*Appropriate patients have normal QT interval, no significant drug interactions with concomitant medications, and no evidence of active or indolent infection with atypical mycobacteria

Mucolytic agents (n-acetylcysteine)

PDE-4 inhibitor (roflumilast)

Systemic glucocorticoids (prednisone)

Acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) are defined as increased dyspnea and/or cough and sputum that worsen in less than 14 days and is often associated with increased inflammation and may be accompanied by tachycardia and/or tachypnea.1,4,8

Preventing AECOPD is important because they contribute to a decline in lung function, poor health status, and increased susceptibility to repeated exacerbation which results in increased morbidity and mortality.

To reduce AECOPD risk:

Watch for the warning signs of a COPD flare up including:

In patients with suspected COPD exacerbation, rule out confounders or contributors:

Choose an appropriate treatment when managing AECOPD:

*Oral, or intravenous if unable to take oral medications. Generally, a 5-day course is preferred.

Potential indications for hospitalization include:

Follow-up within two to four weeks after hospital discharge and again at three-months. Refer to pulmonary rehabilitation as soon as possible after discharge (ideally patients should start the program within one month of discharge).

At every follow-up, assess the following:

At the three-month follow-up:

Patients and their caregivers should receive verbal and written education to support self-management.1-3,8

Written plan that contains guidance for:

Patients with COPD would benefit from a collaborative approach involving providers across a variety of expertise such as physicians, nurses, pharmacists and dieticians to facilitate the implementation of effective management approaches and support self-care to reduce the risk of re-hospitalization and exacerbation, improve quality of life, and reduce mortality. Routine follow up with patients with COPD is essential in identifying and monitoring lung function.9

Follow-up with a respirologist may be considered in those with severe disease, supplemental oxygen dependence and frequent severe exacerbation to consider invasive treatment options.9

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [Internet]. 2023. Available from: www.goldcopd.org

Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (version 3.0). 2021.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. 2019 Jul 26;1–77.

Bourbeau J, Bhutani M, Hernandez P, Aaron SD, Beauchesne MF, B. Kermelly S, et al. 2023 Canadian Thoracic Society guideline on pharmacotherapy in patients with stable COPD. Canadian Journal of Respiratory, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine. 2023 Jul 4;7(4):173–91.

Canadian Pharmacists Association. Compendium of pharmaceuticals and specialities.

Cataldo D, Hanon S, Peché RV, Schuermans DJ, Degryse JM, De Wulf IA, et al. How to choose the right inhaler using a patient-centric approach? Adv Ther. 2022;39(3):1149–63.

Panigone S, Sandri F, Ferri R, Volpato A, Nudo E, Nicolini G. Environmental impact of inhalers for respiratory diseases: decreasing the carbon footprint while preserving patient-tailored treatment. BMJ Open Respiratory Research. 2020 Mar 1;7(1):e000571.

Ontario Health. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Care in the community for adults [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.hqontario.ca/evidence-to-improve-care/quality-standards/view-all-quality-standards/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease

Expert opinion.

The Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease tool was developed using the Centre for Effective Practice’s (CEP’s) integrated knowledge translation approach as part of the Knowledge Translation in Primary Care (KTinPC) Initiative. This approach ensures that clinicians are engaged throughout the development processes through the application of user-centered design methodology. Clinical leadership of the resource was provided by Dr. Anthony D’Urzo. End users and clinical experts were also engaged to provide feedback. Funded by the Ministry of Health, the KTinPC Initiative supports primary care clinicians with a series of clinical tools and health information resources. Learn more about the KTinPC Initiative.

This Tool was developed for licensed health care professionals in Ontario as a guide only and does not constitute medical or other professional advice. Health care professionals are required to exercise their own clinical judgement in using this tool. Neither the CEP, Government of Ontario, nor any of their respective agents, appointees, directors, officers, employees, contractors, members or volunteers: (i) are providing medical, diagnostic or treatment services through this Tool; (ii) to the extent permitted by applicable law, accept any responsibility for the use or misuse of this Tool by any individual including, but not limited to, primary care providers or entity, including for any loss, damage or injury (including death) arising from or in connection with the use of this Tool, in whole or in part; or (iii) give or make any representation, warranty or endorsement of any external sources referenced in this Tool (whether specifically named or not) that are owned or operated by their parties, including any information or advice contained therein.

This Tool is a product of the CEP. Permission to use, copy, and distribute this material is for all noncommercial and research purposes is granted, provided the above disclaimer, this paragraph and the following paragraphs, and appropriate citations appear in all copies, modifications, and distributions. Use of this Tool for commercial purposes or any modifications of the Tool are subject to charge and must be negotiated with the CEP (info@cep.health).

For statistical and bibliographic purposes, please notify the CEP (info@cep.health) of any use or reprinting of the Tool. Please use the following citation when referencing the Tool: Reprinted with Permission from Centre for Effective Practice. (January 2024). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Ontario. Toronto: Centre for Effective Practice.

Developed by: